The Disaster

On the evening of May 25, 2024, an EF3 tornado touched down in Rogers County, Oklahoma. The tornado's path cut directly through Claremore, a city of about 20,000 people northeast of Tulsa.

The damage was concentrated in older, established neighborhoods—areas where homes were often owned by seniors on fixed incomes, families without adequate insurance, and residents who'd lived in the community for decades.

An EF3 tornado has wind speeds of 136-165 mph. At this strength, well-constructed homes lose roofs and walls, heavy vehicles are lifted off the ground, and structures can be completely destroyed. The Claremore tornado was at the upper end of this range.

Impact by the numbers:

- Hundreds of structures damaged or destroyed

- Widespread tree damage blocking roads and crushing homes

- Extended power outages across the affected area

- Disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations

Response Timeline

Recovery doesn't happen in a straight line, but here's how the major phases unfolded in Claremore:

EF3 tornado hits Claremore in the evening. Emergency services respond. Initial search and rescue operations begin immediately.

Road clearing begins. Emergency shelters open. Red Cross arrives. Initial damage assessments start. Media coverage brings national attention.

Mayor Debbie Long begins convening community leaders. Oklahoma VOAD reaches out. Samaritan's Purse and Baptist Disaster Relief deploy chainsaw crews. Local churches mobilize volunteers.

Claremore Regional Community Disaster Alliance (CRCDA) formally organized. Initial stakeholder meeting held. Case management intake process established. First relief applicants registered.

Emergency roof tarping. Tree and debris removal. Mucking and gutting water-damaged homes. Generator fuel assistance. Food replacement for families who lost refrigerated goods. BOUNCE group, Samaritan's Purse, and Baptist Disaster Relief coordinate intensive volunteer deployments.

Transition from relief to recovery. Case management intensifies. Unmet needs meetings begin. Construction projects start. Custom software (Serve.Love Relief Operation) deployed to track cases and coordinate resources.

Recovery operations continue. Complex cases (full rebuilds, insurance disputes) worked through. Volunteer teams from Mennonite Disaster Service and others take on major construction projects.

Survivor Stories

Behind every statistic is a family. These are some of the people the Claremore response served.

Our house was totally destroyed and we spent the first week in the hospital and the next 6 weeks with Ernie in rehab. (We are in our late 80's). Although our family and close friends did much "clean up" we feel truly blessed by your group... What a great act of kindness that just made us feel special.

Melinda's Story: When Insurance Falls Short

Melinda had paid her homeowner's insurance faithfully for decades. When the tornado uprooted a massive tree that now leaned dangerously against her home, she filed a claim.

The insurance company denied it.

Their reasoning? The tree hadn't caused damage yet—it was just threatening to. Until it actually crushed her roof, they wouldn't pay. Meanwhile, Melinda lived in fear every time the wind picked up.

Volunteer chainsaw crews removed the tree at no cost. What insurance wouldn't cover, the community did.

Melinda's story isn't unusual. Many survivors discover their insurance doesn't cover what they assumed it would. This is why LTRs exist—to fill gaps that insurance, FEMA, and personal resources can't cover.

Charline's Story: 99 and Rebuilding

Charline was 99 years old, living on her late husband's Social Security. The tornado damaged her roof—not just cosmetically, but in ways that put her home out of code compliance.

At 99, navigating insurance claims and finding contractors wasn't something she could do alone. Her income left no room for out-of-pocket repairs.

Case managers helped her understand her options. Volunteer crews did the work. Charline got to stay in the home she'd lived in for half a century.

Matthew's Story: No Insurance, No Safety Net

Matthew and his family had no homeowner's insurance. When trees fell onto their home, damaging the roof and leaving massive root balls in their yard, they faced a choice between paying for repairs or paying for everything else.

FEMA Individual Assistance wouldn't arrive for months. No insurance payout coming. Just a damaged home and a family unsure where to turn.

The LTR connected them with volunteer construction teams and material donations. Their home was repaired without sending the family into debt.

Janet's Story: The Hidden Costs

Janet's home was damaged, but her bigger immediate problem was that she couldn't work. The cleanup consumed her days—dealing with contractors, meeting with adjusters, clearing debris.

Without her regular income, basic bills became emergencies. She needed financial assistance just to keep the lights on while she dealt with the disaster.

Emergency financial assistance from the relief fund covered her immediate bills. That breathing room let her focus on recovery without losing everything else.

Organizations Involved

No single organization could have handled this alone. Here's who showed up and what they did:

CRCDA (Claremore Regional Community Disaster Alliance)

The local Long-Term Recovery organization formed specifically for this disaster. CRCDA coordinated all other partners, managed case files, hosted unmet needs meetings, and ensured resources reached families efficiently.

Serve.Love

Technology partner providing the Relief Operation software platform. Tracked all relief applicants, coordinated volunteer scheduling, and enabled real-time visibility into case status and resource allocation.

BOUNCE Group

Local volunteer organization that provided hands-on relief work: debris removal, roof tarping, home repairs. Hundreds of hours of direct service to affected families.

Samaritan's Purse

National faith-based disaster relief organization. Deployed chainsaw crews, heavy equipment, and trained volunteers. Focused on tree removal and emergency stabilization in the first weeks.

Baptist Disaster Relief

Major cleanup support including tree removal, debris clearing, and comfort for homeowners dealing with overwhelming loss. Mobile feeding units supported volunteers.

Oklahoma VOAD

State-level coordination. Connected CRCDA with national resources, provided guidance on LTR formation, facilitated communication between organizations.

Local Churches

Provided volunteer labor, donation collection points, meeting space, and trusted community presence. Many families who might not seek "official" help would accept assistance from their church.

City of Claremore

Mayor Debbie Long was instrumental in convening partners and providing legitimacy to the LTR effort. City resources supported debris removal and coordination.

How Coordination Worked

Coordination is the hardest part of disaster response. Here's how Claremore made it work:

The Unmet Needs Table

Regular meetings where case managers presented family situations and partner organizations pledged resources. A case might be presented like this:

Case #147: Single mother, two children. Roof damaged (tarped but needs permanent repair). Insurance denied claim due to pre-existing condition clause. FEMA application pending but not expected to cover full need. Estimated repair cost: $4,200. Family contribution possible: $500.

Unmet need: $3,700 for materials + volunteer labor for installation.

Partners would then commit resources:

- "We can cover $1,500 from our disaster fund."

- "We have roofing materials available—shingles and underlayment."

- "Our crew can do the install next Saturday."

By the end of the meeting, the case has resources committed. The case manager follows up to execute the plan.

Single Point of Intake

Instead of having families apply separately to each organization, CRCDA created a single intake process. Families told their story once. That information was shared (with permission) across all partners, preventing duplication and ensuring complete needs assessment.

Technology for Visibility

The Serve.Love platform gave all partners visibility into:

- Which families had applied for assistance

- What needs had been identified

- What resources had been committed

- Status of each case (pending, in progress, completed)

This prevented the common disaster response problem of "I thought someone else was handling that."

Technology & Systems

The Claremore response was notable for its use of purpose-built technology. The Relief Operation module within Serve.Love was developed and refined through this disaster.

Key Capabilities

- Relief applicant tracking: Complete record of each family, their needs, and assistance provided

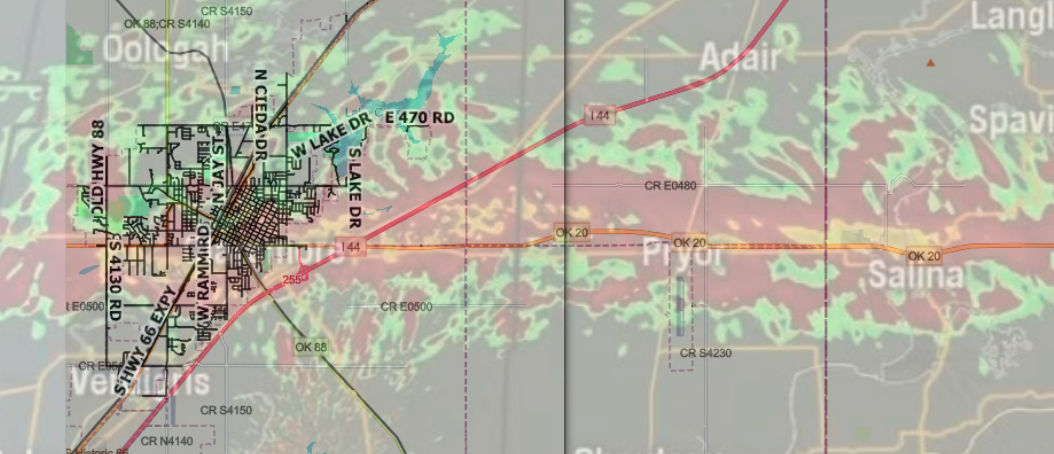

- Geographic mapping: Visual display of applicant locations overlaid on tornado path

- Volunteer scheduling: Coordination of 2,400+ volunteer shifts with skill matching

- Resource tracking: Inventory of available materials and pledged funds

- Reporting: Real-time dashboards for leadership and donors

Why It Mattered

Without systematic tracking, disaster response becomes chaotic:

- Families fall through the cracks

- Multiple organizations duplicate efforts on the same home while others go unserved

- Volunteers show up without work to do, or work exists without volunteers

- Donors can't see impact, so giving decreases

The technology didn't replace human relationships—it enabled them to scale.

Lessons Learned

What Worked Well

Early convening of partners

Mayor Long brought partners together within the first week. This early coordination meant organizations weren't working in silos for months before someone thought to collaborate.

Single intake process

Families only had to tell their story once. This reduced survivor burden and improved data quality.

Faith community engagement

Local churches provided not just volunteers but trusted access to vulnerable populations. Some families wouldn't ask "the government" for help but would accept assistance from their church.

Technology investment

Building proper systems early (rather than relying on spreadsheets) paid dividends throughout the recovery.

National organization partnerships

Samaritan's Purse, Baptist Disaster Relief, and others provided surge capacity that local resources couldn't match.

Challenges Faced

Insurance complexity

Many survivors had insurance but faced denials, delays, or inadequate payouts. Case managers spent significant time helping families navigate insurance issues.

Delayed FEMA Individual Assistance

FEMA Individual Assistance wasn't available in the immediate aftermath. It wasn't until August that FEMA established placement sites and IA funds started flowing—months after the tornado. The early recovery work was done entirely by voluntary organizations and donations.

Volunteer coordination at scale

Managing 2,400+ volunteer shifts is operationally complex. Matching skills to needs, handling no-shows, and ensuring quality work all required dedicated attention.

Long tail of recovery

Six months out, families were still being discovered who hadn't asked for help. Sustained outreach is essential.

What We'd Do Differently

Every disaster response teaches lessons. Here's what we'd change:

Earlier donor communication systems

Donation tracking and donor communication could have been more sophisticated from day one. We built these capabilities as we went; having them ready earlier would have improved donor retention.

More proactive case finding

Some families didn't come forward until months later—often the most vulnerable. More door-to-door outreach in affected areas earlier would have found them sooner.

Better contractor vetting

After disasters, predatory contractors appear. We could have established a vetted contractor list faster to protect families making repair decisions.

Mental health resources integration

Physical needs were addressed effectively. Emotional and mental health needs received less systematic attention. Integrating mental health professionals from the start would improve outcomes.

Apply This to Your Community

The Claremore model isn't unique to Oklahoma. The principles work anywhere:

- Convene partners early Don't wait for "the right time"—start coordinating within the first week.

- Create single intake One application, shared across organizations with survivor permission.

- Engage faith communities Churches and faith organizations reach people who won't seek "official" help.

- Invest in systems Spreadsheets don't scale. Proper case management and volunteer systems do.

- Connect with your VOAD State VOADs connect you with national resources and experienced guidance.

- Plan for the long haul Recovery takes months or years, not weeks. Build sustainability from the start.

Ready to Start?

If your community is facing a disaster, start with our guide to forming a Long-Term Recovery organization.

How to Stand Up an LTR →